I had just turned five that spring.

I had just turned five that spring.

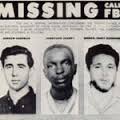

It was a murderous summer. That June 21 in 1964, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney were investigating the burning of Mt. Zion Methodist Church, which had been a site for a CORE Freedom School. Schwerner and Chaney had held voter registration rallies at the church. For that, the parishioners were punished by a number of white men – led, apparently, by Sheriff’s Deputy Cecil Price. Their deacons were pulled out of their cars, placed before the headlights, and beaten with rifle butts. Their church was set afire.

Price found a way to arrest the three men. They were released into a trap: Members of the KKK – also policemen – shot and killed Schwerner, then Goodman, and then Chaney, after chain-whipping him. It took forty-four days to find their bodies. It took forty-one years to convict just one of the men responsible for their deaths.

Last Saturday, it was exactly 50 years since the murders. Two of the men – Michael and Andrew were white, and Jewish. James Chaney was an African American.

Men. Human beings who fought for a heroic cause.

The night before that anniversary I asked my congregation: How could any of us respond to this horror but with silence? These are scenes of brutality and beating, of fear and fire, of terror and murder.

The darkness they elicit is complete. We can respond by going numb, to be sure, but we know it: What happened that day was an example of the human capacity to act evilly. There is hell in the world.

Last Shabbat we read Parsha Korach. There are scenes of fire and death in that parsha, scenes of terror. Our Torah does not make it easy for us; it presents us, repeatedly, with devastating scenes. Humanity goes aground, again and again. God hopes for better and doesn’t get it; Moses and Aaron alternately plead for humanity and find themselves appalled, angry, and depressed. Moses even asks God at one point to end his life; he can’t bear the weight of the responsibility he has shouldered.

And despite the many writers at work, the different time periods the Torah reflects, there is often a strangely linear sense to it all. God commands the Israelites to make tassels, to put these tzitzit on their clothing as a reminder to observe God’s commandments and so, be holy.

Immediately after this command is given at the end of one week’s reading, the next begins with Korach’s challenge: Together with Datan and Aviram and two hundred and fifty leaders of the Israelites, he confronts Moses and Aaron: “Too much is yours! The entirety of the community is holy; why do you exalt yourselves over them?”

Have Moses and Aaron presumed, controlled, become despotic?

Certainly, Moses responds with a test and invokes a cruel judgment for those who fail it. Korach and his followers will make an offering together with Aaron. May the earth swallow those who have rebelled without cause.

But perhaps Moses has second thoughts – he asks Datan and Aviram to come to speak with him, to forestall the conflict? They are intransigent. They refuse, launching yet more accusations. The contest is on.

And the conflagration is near. God is enraged by yet one more example of an ungrateful, recalcitrant people. But Moses and Aaron ask: “If one man sins, will you be furious with all?” Moses begs his community to separate themselves from the rebels – is he sensing that the glove he threw down will lead to utter destruction? Datan and Aviram are surrounded by their wives and children; Korach’s family, it seems, is with him. And just as Moses announced, the earth itself opens up and swallows the rebels. All Israel flees at the sound of their screaming and as they flee, fire comes from before God’s presence and consumes the two-hundred and fifty leaders who had stood with Korach.

The next day, in a state of shock, the people accuse Moses and Aaron of causing the deaths they witnessed. Moses can predict the outcome: A wrathful force will literally plague the people. Again, remorseful, aware that his own pride is part of what has led to this disaster, he says to Aaron, go, go quickly. Make expiation.

And Aaron does so. He stands, the Hebrew reads, between the living and the dead.

How on earth do we reconcile a rebellion with the aftermath endured and witnessed by the innocent? Children die in this rebellion. A plague descends on an entire people.

The three men who died a half century ago were not only innocent of any wrongdoing, but heroes. Their cause was just, righteous, moral in every respect. Their killers acted with a brutality that cannot be gainsaid.

In Korach’s story, there is no hero. Torah will not give us an easy answer. Everyone perpetrates; there are victims of pride, of selfishness, of mean-spiritedness.

Korach insists that all Israel is holy just after the Israelites have been told that becoming holy is a constant challenge, just after God insists that they must dress themselves, each and every day, in reminders of their tasks, their responsibilities, the things they must do in an effort to become holy human beings. Holiness is an aspiration; a call, a hope. Korach is no hero: He has forgotten humility, and that makes him willing to claim prerogative. Just wondering: Have we, as a nation, really earned our right to what we possess? Really?

Moses, embattled and exhausted, asks for doom and gets it: “If these men are guilty,” he says, “let the earth open its mouth and swallow them; let the earth itself speak judgment.” We judge harshly, we invoke punishment. Our words have power. In the movie Chocolat, the mayor remarks: “Someone ought to do something about those gypsies in town.” That night, someone sets their barges afire.

I imagine Aaron in the midst of the living and the dead. Where was our beloved peacemaker? He did not stop his younger brother from invoking judgment. He did not go to Korach and the others. He did not speak on behalf of peace; thus, he was left to stand in the midst of a war zone. The smell of fire must have been everywhere. The sounds of screaming must still have hung in the air. He stood between the living and the dead.

And God? God who read Moses’ judgment script and acted it out? God who threatens to destroy (again) the people he saved? God can be appeased by human beings, but God cannot be excused.

It is a story of hell in the world.

A few weeks ago, I was present when a colleague of mine asked her congregation: There is hell in the world: What does liberal theology have to say in response?

Hell has a spectrum – from the rebellions and discontents that build tension and anger and frustration in families, in communities, in church and synagogue. There is hell in our easy judgments. We call for more time in prison for the murderer or even his death, and one day we read about an attempted execution so brutal that the victim suffers agonies for forty five minutes and dies later of a heart attack.

Our nation goes to war in faraway lands and the children who survive go to work clearing mines and losing limbs.

The spectrum is wide and deep. We have only our tassels. Most of us are not heroes.

But our tassels are signs of hope and commitment. We must strive for holiness in the world. This is how we can, as my colleague said, “love the hell out of the world.” We can create a spectrum of kindness of love, of generosity, of understanding. We can look for opportunities to wear our tassels, to make heaven on earth.

So we must.